The Outback, including Hughenden, is a fine place to visit. Its sweeping plains, its never-ending blue sky, its sunsets but most importantly its people. A few days of exploring and embracing the country pace of life before being swept away back to the familiar. For some though it’s a lot more, it’s home and as the old adage goes ‘the people make the place’.

Australia boasts a rich tapestry of cultures and people. From older to younger and from all over the globe. Hughenden is no different, but our smaller, tighter-knit community ensures we know each other that little bit better and can put names to faces. It’s all part of the charm of outback living.

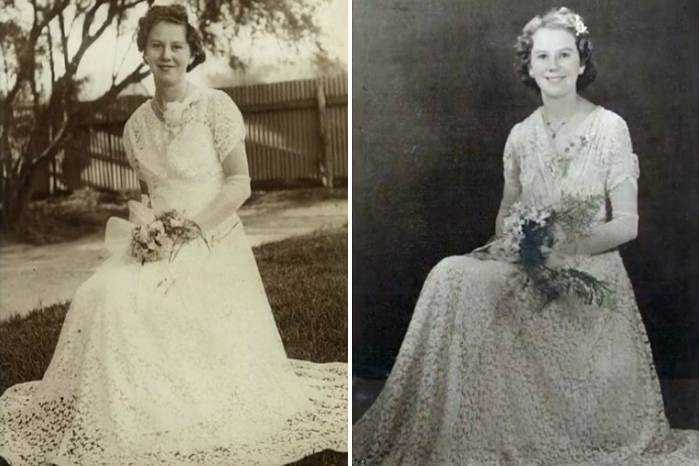

With that in mind, at Hughenden, we recently celebrated a very important milestone. Joyce Price turned 100 years old. Perhaps it’s a testament to clean air and good country living or perhaps it’s in Joyce’s character, humour and the resolve needed to face the challenges of the last 100 years. Joyce’s life is as ‘full’ as you can imagine; grazier’s wife, teacher, grass-roots politician, mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. We thought we’d share some of Joyce’s life, after all, her story is a part of Hughenden’s story and across the span of her life, we get a glimpse into our history.

___

This article is sourced using “Older Folks of Finders Shire”.

Joyce first came to Hughenden in 1935. Her paternal grandfather, Henry Alfred (Harry) Hawthorne, had opened a saddlery and leather goods business in what is now Sourry’s Newsagency sometime earlier.

Her parents Stuart and Gertrude Hawthorne, and then three-year-old sister Eileen followed soon after. Originally they planned to stay three months to settle her grandfather’s affairs. Joyce and her brother Cyril were left in Maryborough to finish out their school year. The three-month trip was extended indefinitely and Joyce was again left behind as she was already in high school.

“I first came to visit Hughenden for the Christmas holidays in 1936. It was then I discovered that my brother’s stories of goats, flies and screeching galahs had more substance than imagination.”

Joyce’s father worked as a saddler, then on the railway and then as a steward at the Flinders Club in the 1950s.

“It was nonetheless good to be back with family and when I graduated from Teachers’ Training College in 1939 I applied for and was granted an appointment in Hughenden.”

“One lasting memory from my early visits was that of the Chinese gardener See Lee, who hawked his wares in a horse-drawn cart. The horse was bedecked with a straw hat.

In 1940 Joyce made the move to Hughenden and started teaching.

“My most memorable day was in 1942. The bombing of Pearl Harbour, followed by the fall of Singapore set in motion a sensational exodus of women and children from the coast.

“They filled the verandahs, streamed down steps and were even queued in the playground. A second admission site was soon established but it was recess before the last parent was farewelled.”

The impossibility of the situation became apparent when the sheer number of students became known. Desks and extra staff were needed. A phone call to Brisbane ensured that both teachers and desks would be on their way from Townsville. However, by the end of 1942 many that the exodus had displaced returned to the coast. Hughenden was able to keep one of the extra teachers and the desks.

“Still trenches were dug around the western playground and air-raid drills became part of the school routine.”

“One sad feature of those days was the number of talented children, who were unable to carry on with their studies.”

In 1944 Joyce was transferred to Gordonvale. After deciding she missed Hughenden, Joyce arranged to exchange places and was back to teaching in Hughenden in 1945. This same year she married George Price and went to live at Hillview Station.

“Country living was a complete change and culture shock for me. I had never lived without electricity and although I remembered my grandmother using Mrs Potts iron, “I had not expected ever to do likewise. The alternative was a petrol iron, which was so terrifying if the lighting process went wrong that I developed a real affinity with Mrs Potts, before we acquired a 32-volt lighting plant in 1950.”

Due to the rising price of wool in the 1950’s the young couple were able to make some improvements and a house bore and lighting plants made life easier. But Joyce warned it never paid to be too comfortable.

Winter rain in 1951 spoiled all the Flinders grass and the long-awaited 1952 wet season never came. At Easter time that year, the couple bought Cheltenham, a desert block 24 miles from Torrens Creek.

Joyce remembers that her husband George and a station hand drove the sheep down from Hillview Station to Cheltenham. They soon set about resurrecting the abandoned house. By this time the couple had two children: George Stuart born in 1947 and John Vivian born in 1949.

“We set off in the Bedford truck carrying everything including the kitchen sink. If I had thought moving to Hillview was a culture shock, living at Cheltenham was out of this world.

“There was no power; no running water; no floor coverings. And George’s idea to make the building habitable was to jet it inside and out with Cooper’s dip. It was literally back to basics.”

However, the young family survived, and when it finally rained in 1953, they returned to Hillview.

“Imelda Mary was born in 1954. A girl at last. Kevin James was born in 1959 and that completed our little family.”

The family enjoyed eight years at Hillview but the dry conditions returned in 1962. Joyce and her family returned to Cheltenham with their sheep, this time the house there had been completely demolished. So George regularly commuted 100 miles between the two properties. Rain brought the sheep and George home in March.

A great leap forward for station life occurred in 1965 with the advent of town power. Sadly, it was a mixed time for Joyce with her father-in-law passing away just before the connection. Joyce was able to enjoy the conveniences of life more after that: No more smoking kerosene refrigerators and no more going out in the cold at night when the power plant cut out. Joyce’s husband George’s health took a turn for the worse a short time after.

“My husband’s health began to deteriorate shortly after his father’s death. As our sons finished school he became more and more dependent on them to do the physical work on the property. New Year’s Day 1970 when we learnt he had cancer. Surgery was performed but it was too late. We lost him three years later.”

Joyce stayed on at Hillview with her then-married children George, John and Imelda. Tragically Kevin was killed in a car accident in 1988. Joyce’s other sons George and John were also taken before their time.

“Prolonged drought, the collapse of the wool market and the need to educate the third generation on a low income have taken its toll, but I have lived a comfortable life. It has been my great pleasure to know and love seven grandsons, one granddaughter and three great-grandsons.”

Since this article was published, Joyce’s extended family has grown to 8 grandchildren and 21 great-grandchildren.

Joyce has been an incredible influence on many in the community, including our Mayor, Jane McNamara. Joyce was responsible for getting Jane into politics and has been an unerring but positive influence throughout her life.

“Joyce was more like a mother than an aunty to me growing up, and we have developed a great friendship.”

“When Joyce was in her mid 90’s I asked her to live with me as her mobility issues increased. Joyce lived with me at the townhouse while she could and now resides at the Hughenden Hospital.”

Joyce Price has outlived her three sons, Kevin, John and George Jnr, and her husband George Snr. Her daughter Imelda is her only surviving child.

“Through family tragedy, she has shone. Joyce has faced her share of hardship in her time but always has a wicked sense of humour, and she is the queen of one-liners.”

When Joyce was asked what the secret of her longevity is, the running joke in the family is that it is most certainly not vegetables. One of the other residents at the Hospital called her out on it and Joyce called her ‘nothing but a ‘dibber-dobber’.

As a person of faith, Joyce has questioned why ‘God doesn’t want me yet, he’s only taking me one tooth at a time’.”

In a recent article featured in the ABC (here), Joyce cheekily claims that ‘behaving yourself’ is the key, but her daughter Imelda said that her mother’s love of treating herself may have been the secret claiming “Sugar, salt and Scotch” have their virtues as a staple diet. A philosophy we’re all happy to subscribe to.

Sources/ Further reading

“Older folks of Flinder’s Shire”